- Home

- Robinson, Garrett

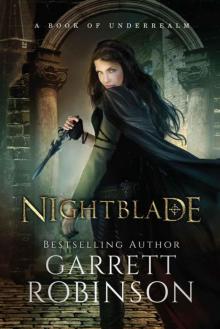

Nightblade: A Book of Underrealm (The Nightblade Epic 1) Page 8

Nightblade: A Book of Underrealm (The Nightblade Epic 1) Read online

Page 8

Annis sat dumbfounded. “Can cloth truly bend iron this way?”

“Would I lie to you?” A small smile played across Loren’s lips.

Yes. Yes, I would, and I have.

She felt no obligation to tell Annis everything. Let the girl feel the frustration of a bad tale.

Annis shook her head. “No. I cannot believe it. Else how could any prison hold its captives?”

Loren shrugged. “Believe it or not, as you will. I tell only an old tale.”

“What value has an old tale without a kernel of the truth? What else are stories for?” Annis folded her arms, pouting.

Loren had tired of her little performance. “I am sorry to have disappointed you. But now I must go. I have had much water as I walked, and it is now begging leave.”

“I shall accompany you,” said Annis, leaping to her feet.

“You? What happened to refined society, where we must hide our bodies away?”

Annis shrugged. “It grows dark. If you object, we may take turns.”

Loren grimaced, but she could do nothing. Together, they tramped toward the trees, Gregor shadowing their footsteps. Once they had passed between the first two trunks, Annis turned to look at the captain.

“You approach far enough,” she said.

Gregor did not blink. “Your lady mother commands me, Annis. Not you.”

“And what will my mother think, if I tell her that you leered at me like an old lecher when I went to relieve myself?”

Gregor did not reply, or move a muscle. But when Annis turned and walked on, he followed farther back. When they stopped, he fell out of sight. But he did not fool Loren—she knew Gregor’s men lurked all around them. She gave a grumbling sigh and prepared for her business.

“We must speak, and quickly,” whispered Annis. “And for the love of decency, do not do that while I stand here.”

Her urgent tone drew Loren’s attention. “What of?”

“You are in danger as long as you stay here.”

Loren snorted a grim laugh. “You bring me no news. Your mother seems to see little value in any life, much less my own.”

Annis’s eyes stayed solid. “I believe my mother keeps you here as a distraction.”

“For what?”

“I have heard her speak with Gretchen in the carriage. If questioned, my mother will tell the city guard that yesterday’s constable pursued you north along the road. But if that should fail, they will likely search our wagons. Then Mother will change her tune. I think she means to trade you in exchange for safe passage into the city.”

Loren swallowed hard. It hurt her throat. “Why tell me?”

“Do you think I resemble my mother?” whispered Annis, glaring at her. “She has fed many men to the darkness below, ever since I was a babe. I was raised to think it an ordinary thing. Then one day, I learned the truth: that murder was wrong, and outside the King’s law. My mother only escaped justice thanks to the depth of our coffers. I have sought to break free from her ever since.”

Loren could say nothing, knowing much of the desperation to escape home.

Annis looked into her eyes. She must have seen something to encourage her. A stern, set expression crossed her features. And again, she spoke in a whisper. “Will you do it, then? If I help you escape, will you take me with you?”

“I will.” Loren nodded. “I swear it.”

thirteen

As they traveled on the next morning, Damaris emerged from her carriage.

“Loren.”

As soon as she heard the merchant’s high voice, Loren’s heart leapt into her throat. She pictured Annis’s face glowing blue in the moonslight. Had it all been a ruse? Perhaps Annis had told her mother everything, and now Damaris summoned Loren for judgement.

But no. They could have done that last night. Gregor could have ended her in an instant at any time. While Loren still lived, she must keep hope. So she sped her pace to join the merchant.

Today, Damaris wore a gown of light green. It hung slimmer than her average garb, though that by no means rendered it plain. Elegant designs like spiderwebs wound up and down its length, some in gold thread and some in light pink, interlocking to create a varied palate of color. Her hair clung to the top of her head in tight braids, worked into a wide bun.

But the merchant’s beauty no longer impressed Loren, for she had seen what lay beneath. Only a fool saw a bear trap wrapped in velvet and still desired to run their hand along it.

As Loren came to her, Damaris took the edge of the black cloak in her fingers and ran them along its trim, an eerie smile playing on her lips.

“It suits you very well. Do you enjoy it?”

Loren chose her words carefully. “I have often dreamt of a cloak just like it.”

That was true enough. In Loren’s dreams, Nightblade always wore a cloak of fine black cloth.

“It will serve well for riding, as well as foot travel,” said Damaris. “Gregor, bring my horse.”

Loren was taken aback. What did Damaris play at? She mocked her for objecting to the constable’s death and then caressed her and gave her a fine cloak. She put Loren under guard like a common criminal but continued her riding lessons.

“My lady is too kind,” said Loren.

Damaris nodded and stepped aside.

This time, Loren mounted more easily and sat loose, hands firm on the saddle horn. Gregor mounted his own steed and came forward to take the reins from his lady.

Thus we walk down the road together, as pretty a picture as one could imagine. The captain, the merchant, and the forester’s daughter.

It sounded like the name of a song, but Loren could not find a smile at the thought. Even being back on horseback could not improve her mood. Damaris had poisoned the dream.

“That dagger at your belt,” said Damaris. “A fine make, is it not? Gregor, you know of such things.”

Gregor did not bother a glance. “A fine make indeed, my lady.”

“I confess my curiosity as to how you came by it,” said Damaris. “An heirloom, perhaps, passed down from your family’s nobler days?”

Loren shrugged. “I see only a knife, my lady.”

“Oh, no,” said Damaris. “No, not only that. To the wise and trained eye, that dagger holds more words than a tome. It speaks of breeding, of artistry. If I did not know better, I would say you had taken it from a corpse—” she gave Loren a sharp glance, “—but of course we have seen how abhorrent you find such things.”

“It came from my parents,” said Loren, her voice cool, nonchalant. “Where they came by it, I never knew. But when I left home, it passed into my hands. I made a vow to use it honorably.”

She put a small bite in the last word, hoping to anger Damaris with the dig. But if the merchant noticed, she gave no sign.

“Curiouser and curiouser,” said Damaris. “And how came simple foresters by such a fine thing? Perhaps my guess of grave robbery falls near the mark, though it may not have been you who did the robbing.”

Now came Loren’s turn to feel the bite of words well chosen. Her cheeks flushed, and she found herself surprised by her anger. What did she care for insults delivered to her parents? She had thought much worse than that in fifteen years.

“Oh, do not take such offense,” said Damaris, tossing her hair. “I jest. And even if your parents acquired the dagger through . . . less than savory means, what of it? I do not know the tale of how my forebears came by their wealth, but I doubt that book is free of darker chapters.”

“Is that why you act the way you do, my lady? Are you only following in the footsteps of your ancestors?”

“Do any of us do different?”

“I will never be like my parents.”

“So have said all of history’s children. But if they only considered things clearly, they might not see their parents as villains after all. Take Annis, for example. She does not approve of many things I do to ensure her safety. Did she tell you?”

Loren felt su

ddenly glad for years of experience lying to her parents. Not a muscle in her face twitched. “No. She seemed quite cheerful, in fact, after . . . after what happened.”

“A farce she puts on to hide her disgust, I fear,” said Damaris. “Yet I would go to any length for her future, to depths twice as black as you can imagine.”

“You did it to protect her, then? Would the constable have killed a little girl if he found your cargo?” Loren could not quite keep the bitterness from her voice.

Damaris shrugged. Loren had the urge to kick her. “They would have spared her. But safety means more than survival; true safety lies only in plenty, and sometimes not even then. Do you know how long the nine lands have had a High King?”

Loren frowned at the unexpected change in topic. She thought hard. “Two thousands of years.”

“Twelve hundreds,” said Damaris. “And the kingdoms have changed mightily in that time. The men who laid the rules of election and first drew our borders would not recognize the lands we walk today. Nine royal families there are, but none of those families existed when the High King first took his seat. But do you know how long my family has dealt in our . . . unique brand of goods?”

Loren did not wish to seem foolish by answering wrong, so she remained silent.

“Twenty-six hundreds of years. We claim to be the oldest family in the nine lands. Vast is our wealth and extensive our power. Kings claim the right to rule, but their right has only ever come from coin. Coin that my family, and others like ours, control. Even as a lesser scion of my house, I may yet have the ear of any man in the nine lands, save only the High King himself, if I so desire.”

Loren’s body had tensed. She forced herself to relax and move with the horse. What manner of people had she fallen in with?

“Do you know that there has never been a Merchant’s War?” said Damaris, again shifting subjects like the wind. “Neither in name, nor in practice. Wars are brutal, messy things, far below our station. Yet men insist upon fighting them, and we are only too happy to lend them the coin. But while we do not go to war, that does not mean we have forgotten the benefit of a swift killing. We deal death in dark and silence, the bodies quickly buried and more quickly forgotten. Many know of it. None acknowledge it. As long as it remains well out of sight, most would sooner ignore it. Thus it has always been, and thus it will always be. Do you understand?”

Loren could not begin to understand. But she nodded quickly atop the horse. “I do, my lady.”

“I doubt it. But one day, you might.”

Loren knew it would be better to still her tongue, but she could not avoid one question. “My lady, why do you tell me all this?”

“Because,” said Damaris, “I see precious things in your eyes, child. So much fear and anger, well met with wonder. You have suffered much, and yet you still believe the world can hold more than suffering. Who has not felt the same? Girls such as yourself are like pure white eagles found in the woods; rarer than elves and twice as sacred, treasures we must preserve at all costs.”

The flowery words drifted though Loren’s mind like a dream. She remembered Annis’s words and tried to find her senses. Damaris sought to flatter her so she could be more easily deceived. She would not fall prey to such a simple scheme.

And as she thought on them, Damaris’s words touched off a thought in Loren’s mind.

Damaris clucked her tongue. “Come, try trotting again.”

Gregor spurred his horse and tugged on Loren’s reins. Both beasts erupted into motion and trotted off together, Loren clinging to the mount’s neck, glancing every so often at the sword at Gregor’s belt.

That is the truth of this world. Not flowery words, but a large man with a blade at his waist.

fourteen

The final morning dawned, the day upon which they would reach the walls of Cabrus. Loren woke earlier than normal, when the sky held only a tease of grey with no trace of blush.

She looked up and, for once, did not see Gregor standing nearby. So the giant did sleep. She rose and took a hesitant step from the caravan. A guard melted from the darkness to watch her.

She could not shake a persistent feeling that nestled between excitement and apprehension. Today, her journey with the caravan would end in one of three ways: Loren would escape, the constables would take her prisoner, or someone would kill her.

Kill me.

The thought that she might die today did not cause her nearly as much worry as she thought it might. After witnessing eight men murdered, death seemed common, a trite thing, almost too often done.

Gregor appeared, and the other guard vanished into the diminishing darkness. Soon after that, Annis emerged from her carriage. She stretched and yawned in the early light, her eyes finding a sparkle as they fell upon Loren.

“Good morn! We reach Cabrus today.”

“So I have been told.” Loren had decided the day before that she must maintain an air of sullen silence and resentment around Annis. Gregor must not suspect the girls of plotting. Annis, for her part, seemed to understand, for she wore the same chipper, vacant smile she had worn upon the constable’s slaughter.

“Come,” said Annis. “Let us visit the woods before we set off. You may not see them again for a while, I fear, and you have spent your life among trees.”

“I suppose.” Loren laid the waterskin in her travel sack and slung it over her shoulder. The sack bulged with provisions. The waterskin sloshed full and noisy, refilled from the caravan’s stores.

Annis held her chatter as they came under a swath of tree boughs, the now-blushing light bathing her upturned face and somewhat squashed nose. After a spell, she turned to Gregor. “I need my privacy.”

He nodded slowly and gestured at Loren. “Very well. Come with me, girl.”

“Not from her,” said Annis. “We are maidens both. Besides, dawn rises—she must need to relieve herself.”

Loren shrugged, giving Gregor a dead-eyed stare. “I suppose.”

Gregor backed off, none too pleased. Annis pretended to squat, and Loren joined her.

“Our time runs short,” said Annis, her voice a low whisper. “Today we must escape.”

“I have an idea.”

Annis blinked in surprise. “Truly? Tell me.”

“If I can distract Gregor and his men, can you acquire one of your mother’s brown cloth packages?”

Annis blanched. “Perhaps, but why?”

“Damaris told me that the world runs smoothly as long as no one must face the deeds of her and her kind. I plan to turn things rough.”

Annis shook her head. “If I am caught . . . ”

“I can provide ample distraction. Can you do it?”

“I can.” Annis did not sound pleased.

“Good. Come, then. Let us return, for we must act before the caravan moves on.”

They made their way back. In only a moment, they spotted Gregor through the trees. He watched them with an unreadable expression, trailing in silence.

Once they neared the road again, Annis bid Loren farewell and headed off on some pretense of preparing her carriage. That left Loren and Gregor alone. Loren increased her pace, making for the third caravan from the end—the only one she knew for certain held the brown cloth packages.

“Where are you going?” said Gregor.

Without meeting his eyes, Loren said, “Oh, nowhere of consequence. Tell me, when did you learn swordsmanship?”

Gregor did not answer.

“Come, now. Surely no harm can come from my knowing. Were you as old as me? Younger? Older?”

Gregor sniffed. “Younger. I began my training as a boy of ten summers.”

“Ten!” Loren allowed shock to claim her face. “Then you have the advantage. I greatly desire to learn how to protect myself. Could you teach me?”

Gregor did not answer.

Loren spotted a guard near the wagon, standing near its head. She made for him quickly, her pace just below a run. “If I wish to catch up, I must start

immediately. Do you think you can teach me what you know today, before we reach the city walls?”

“I trained for years,” said Gregor, now with an undercurrent of exasperation.

“I fear I have no years to waste on such an endeavor. We must speed the process.”

The guard noticed them at last, looking up in confusion. Without warning, she sprang forward and dragged his sword from its scabbard. The man shouted in alarm, but Loren danced away on the balls of her feet. The sword felt much, much heavier than she had expected.

“How do you manage such a thing? I can scarcely lift the blade!”

“Drop it.” Gregor’s hand shot to his sword, scowling. The guard came after her, arms outstretched, but Loren turned and ran another few steps.

“I mean no harm! I wish only to learn!”

She must not appear a threat. Loren had no desire to end this day on the end of Gregor’s blade. She danced down the line of wagons, waving the sword in the air in what she hoped passed for an imitation of a true fighter. “Come! Teach me the intricacies of parry and thrust, the elegant dance of death!”

She let her feet tangle beneath her and crashed to the ground, careful to land away from the blade. The guard leapt forward, but Loren shot to her feet, just out of reach. It was a dance, she realized, though her partner seemed unwilling. She took a fighter’s pose, one arm behind her and the sword held forward.

“Now, how does one manage the thrust?” She tried it, and the guard cried out as he fell back. He stumbled over his heels, barely managing to stay his footing.

“If you do not drop that weapon—” said Gregor.

“You will take it from me? I welcome it! Come, teach me the way they taught you as a boy!”

Nightblade: A Book of Underrealm (The Nightblade Epic 1)

Nightblade: A Book of Underrealm (The Nightblade Epic 1)